Recently at Planet 9 Energy, I had to setup a VPN access to secure some of our internal services. One of the requirements was to make the provisioning easy to reproduce over multiple environments, so we ended up playing a bit with Terraform, while obviously adopting OpenVPN for the VPN server.

Another important requirement was to expose the OpenVPN web interface (also called Access Server) using an SSL, which I was expecting to be one of the most challenging things to automate, instead, it turned out to be very easy using Let’s Encrypt and Certbot.

In this article, I will illustrate you how to use Certbot to automate the creation of SSL certificates (for OpenVPN as a practical example) and how to integrate this process in AWS-land using Terraform.

Installing Certbot

Installing Certbot on a Ubuntu (Xenial) machine is as easy as:

sudo apt-get -y install software-properties-commonsudo add-apt-repository -y ppa:certbot/certbotsudo apt-get -y updatesudo apt-get -y install certbotThis code uses the certbot PPA to install the executable.

A Little tip (in case you don’t know it yet): -y allows the install to be non-interactive and to proceed without the need to confirm every operation from the keyboard.

From this moment on you can use the certbot executable.

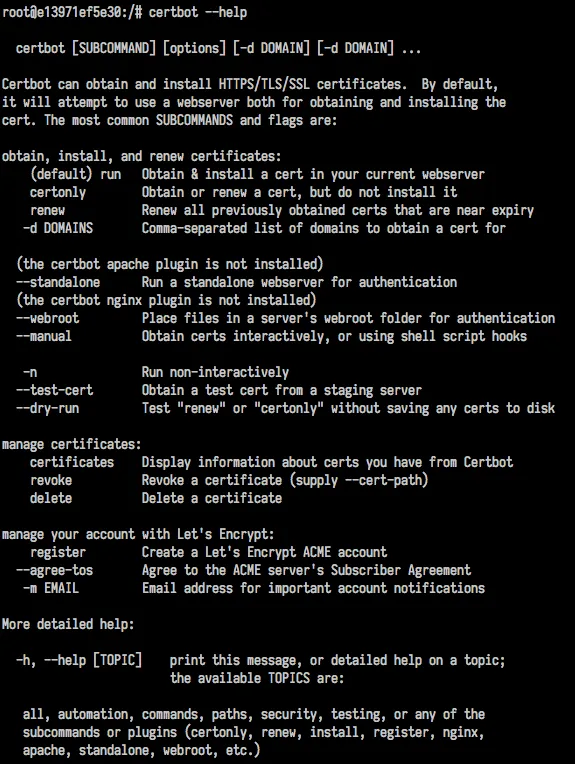

If you want to have an idea of its capabilities you can simply run:

certbot --helpThe outcome will be something like this:

Generating a certificate with Certbot

Certbot uses Let’s Encrypt to generate a certificate. Let’s encrypt issues a certificate for your domain only if able to verify that you really own that domain and that it is associated with the public IP of the machine from which you are running certbot.

So, in order to pass the verification process, you need to have a web server running on your machine and accessible from the outside world. While Certbot supports the main web servers such as Nginx and Apache, it also features a standalone server that you can use exclusively for the verification process. This web server will run on the standard web ports (80 and 443), so if you have other services using these ports you need to stop them first.

In the case of OpenVPN you can stop its web server with:

sudo service openvpnas stopThen you can run certbot command line with the following options:

sudo certbot certonly \ --standalone \ --non-interactive \ --agree-tos \ --email YOUR_CERTIFICATE_EMAIL \ --domains YOUR_DOMAIN \ --pre-hook 'sudo service openvpnas stop' \ --post-hook 'sudo service openvpnas start'Let’s see briefly what every option is doing:

--standalone: runs the standalone web server for the verification process.--non-interactive: runs in totally automated mode, never asks for input.--agree-tos: needed to make the above work, with this parameter you are confirming you agree to the terms of service.--email: the certificate email.--domains: the certificate domain.--pre-hook: this is needed for the auto-renewal of the certificate and describes what is the command to run before the renewal process can be executed. We are using it to stop the OpenVPN web interface.--post-hook: similar to the previous one, allows us to specify a command to be executed after a certificate is renewed, we use it to restart the OpenVPN web interface.

This command generates numerous files including server.crt and server.key, the two files we need to use in OpenVPN. So let’s link them into the proper OpenVPN folder:

sudo ln -s -f /etc/letsencrypt/live/YOUR_DOMAIN/cert.pem /usr/local/openvpn_as/etc/web-ssl/server.crtsudo ln -s -f /etc/letsencrypt/live/YOUR_DOMAIN/privkey.pem /usr/local/openvpn_as/etc/web-ssl/server.keyWe link them because they will be changed in the future by the renewal process, so we are sure that OpenVPN will be always using the most updated certificate files.

And, finally, we can restart OpenVPN:

sudo service openvpnas startAfter few seconds your OpenVPN website should be up and running, and with a shiny green icon indicating that the website is properly encrypted through a signed certificate, woohoo, well done!

A complete example infrastructure with Terraform

I am happy to share with you a simplified version of my Terraform OpenVPN project, to give you an example of how you can use the aforementioned details in a Terraform context.

All the code available in the following section is also available as a repository on GitHub.

Let’s start with a list of the AWS resources we need in order to provision a fully functional OpenVPN:

- A VPC (Virtual Private Cloud)

- One or more subnets in the VPC

- A EC2 instance to host OpenVPN

- A key pair to be able to SSH into the OpenVPN machine (for maintenance or troubleshooting)

- A security group (to enable traffic inside and outside the EC2 instance)

- A DNS record in Route53 to expose our VPN in a subdomain

Quite a few things to be honest, but the declarative nature of Terraform will make things easy.

Let’s create a file called openvpn.tf and let’s start to add things there:

VPC & Subnet

Let’s create the VPC and the subnet:

variable "vpc_cidr_block" { default = "10.0.0.0/16"}

variable "subnet_cidr_block" { default = "10.0.0.0/16"}

resource "aws_vpc" "main" { cidr_block = "${var.vpc_cidr_block}"}

resource "aws_subnet" "vpn_subnet" { vpc_id = "${aws_vpc.main.id}" cidr_block = "${var.subnet_cidr_block}"}Here we are using two variables vpc_cidr_block and subnet_cidr_block that can be easily reassigned from the outside to change the configuration if needed. By default, we are creating a VPC on the 10.0.0.0/16 IP range and a subnet spawning over the full VPN (same IP range).

The rest of the code describing the VPC and the Subnet resources should be pretty self-explanatory.

The key pair

Let’s create now the SSH key that we can use later in case we want to SSH into the OpenVPN machine.

variable "public_key" {}

resource "aws_key_pair" "openvpn" { key_name = "openvpn-key" public_key = "${var.public_key}"}Basically we are only defining here a aws_key_pair resource and specifying a name and the public key.

Public key is a string that comes from the variable public_key.

Most of the time you will be creating a dedicated key with the following command:

ssh-keygen -f openvpn.keythis will create openvpn.key (private key) and openvpn.key.pub (public key). The first one is the one we would reference here.

If we want to reference the content of a file we can use "${file("openvpn.key.pub")}" to assign a terraform variable.

Security group

Let’s create our security group:

variable "ssh_port" { default = 22}

variable "ssh_cidr" { default = "0.0.0.0/0"}

variable "https_port" { default = 443}

variable "https_cidr" { default = "0.0.0.0/0"}

variable "tcp_port" { default = 943}

variable "tcp_cidr" { default = "0.0.0.0/0"}

variable "udp_port" { default = 1194}

variable "udp_cidr" { default = "0.0.0.0/0"}

resource "aws_security_group" "openvpn" { name = "openvpn_sg" description = "Allow traffic needed by openvpn" vpc_id = "${aws_vpc.main.id}"

// ssh ingress { from_port = "${var.ssh_port}" to_port = "${var.ssh_port}" protocol = "tcp" cidr_blocks = ["${var.ssh_cidr}"] }

// https ingress { from_port = "${var.https_port}" to_port = "${var.https_port}" protocol = "tcp" cidr_blocks = ["${var.https_cidr}"] }

// open vpn tcp ingress { from_port = "${var.tcp_port}" to_port = "${var.tcp_port}" protocol = "tcp" cidr_blocks = ["${var.tcp_cidr}"] }

// open vpn udp ingress { from_port = "${var.udp_port}" to_port = "${var.udp_port}" protocol = "udp" cidr_blocks = ["${var.udp_cidr}"] }

// all outbound traffic egress { from_port = 0 to_port = 0 protocol = "-1" cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"] }}By default, this Security group allows access from every IP address using the ports 22 (SSH), 433 (HTTPS) and all outside traffic. It also enables the traffic needed for the OpenVPN protocol both on TCP (port 943) and UDP (port 1194). In case you want a custom setup, you can redefine all the relevant variables here (but in that case you might need to customise also the OpenVPN settings, a step which is not covered in this article).

Subdomain

Let’s now create the subdomain from where our VPN will be accessible.

variable "route53_zone_name" {}variable "subdomain_name" {}

variable "subdomain_ttl" { default = "60"}

data "aws_route53_zone" "main" { name = "${var.route53_zone_name}"}

resource "aws_route53_record" "vpn" { zone_id = "${data.aws_route53_zone.main.zone_id}" name = "${var.subdomain_name}" type = "A" ttl = "${var.subdomain_ttl}" records = ["${aws_instance.openvpn.public_ip}"]}In this part of the code, we are defining 3 variables:

route53_zone_name: the name of your main domain zone (e.g. “example.com.”, notice the dot at the end).subdomain_name: the name of the subdomain to use for the VPN (e.g. “vpn.example.com”).subdomain_ttl: the TTL for the domain (60 seconds by default).

Then, we create a reference to the Route53 zone using the data syntax.

Finally, we create the record in the zone using an aws_route53_record resource.

Notice that we are referencing here the EC2 instance public IP, which we haven’t defined yet.

EC2 instance

Let’s see now how we can define the EC2 instance that will host the OpenVPN software for our virtual private cloud:

variable "ami" { default = "ami-f53d7386" // ubuntu xenial openvpn ami in eu-west-1}

variable "instance_type" { default = "t2.medium"}

variable "admin_user" { default = "openvpn"}

variable "admin_password" { default = "openvpn"}

resource "aws_instance" "openvpn" { tags { Name = "openvpn" }

ami = "${var.ami}" instance_type = "${var.instance_type}" key_name = "${aws_key_pair.openvpn.key_name}" subnet_id = "${aws_subnet.vpn_subnet.id}" vpc_security_group_ids = ["${aws_security_group.openvpn.id}"] associate_public_ip_address = true

# `admin_user` and `admin_pw` need to be passed in to the appliance through `user_data`, see docs --> # https://docs.openvpn.net/how-to-tutorialsguides/virtual-platforms/amazon-ec2-appliance-ami-quick-start-guide/ user_data = <<USERDATAadmin_user=${var.admin_user}admin_pw=${var.admin_password}USERDATA}In this piece of code we are defining some variables:

ami: the id of the AMI (Amazon Machine Image) to use to run the EC2 instance. The default one is a Ubuntu Xenial OpenVPN machine that runs on the eu-west-1 region (Ireland). Feel free to select another image that might suit your needs best.instance_type: the type of instance. You can check the list of all the type of EC2 instances to understand which one might be the best for you. The default here is ok for most of the use cases.admin_user,admin_password: The username and password of the admin user for your VPN.

Whit all those variable in place, we can describe a aws_instance resource. Notice that we are defining it so that it will be bootstrapped in our VPC and in the subnet we specified before. Also notice that we are setting associate_public_ip_address to true, this way the machine will get a public IP (the one we will associate to the subdomain defined earlier).

Finally we define a user_data property. EC2 User Data allows to provide extra configuration code that is executed as soon as the machine is bootstrapped. It is generally used to install extra software, start some service or edit configuration values. In our case, since our image already contains OpenVPN, we use it only to provide the credentials for the default OpenVPN admin user.

Trigger-based provisioning with null_resource

At this point we created all the resources we need and the OpenVPN admin can be already accessed by pointing the browser to your custom subdomain (using the HTTPS protocol).

If you try to do that though, you will get a warning page saying that the certificate for this domain is not valid. This is because OpenVPN is using an auto-generated self-signed certificate which is not bound to your domain, neither signed by a trusted authority (such as Let’s Encrypt).

So let’s do the interesting bit here, adding a Let’s Encrypt certificate for our subdomain!

If you got the basics of Terraform and AWS here you might think that we can do this by simply adding few lines to our EC2 User Data script. While this, in theory, is not wrong, is not going to work in this case because of the way our resources here depend on each other. Let’s clarify exactly why…

So in our current situation, we have to respect the following order of creating resources:

- Create a VPC

- Create a Subnet in the VPC

- Create a key pair and a security group

- Create an EC2 instance

- Create a subdomain record pointing to the public address of the EC2 instance

- (TODO) Create the certificate and install into the current OpenVPN instance

So, the subdomain record can be created only after the EC2 instance is running and it has got a public IP address, only then we have a valid domain that we can use for the certificate. This means we cannot use the EC2 provisioning step, but we need to have a “trigger” that tells us when the subdomain is available and do some extra stuff.

Terraform is smart enough to reconstruct the dependency graph of all our resources and to create the resources in the right order, so we don’t need to worry about that and we can keep loving the declarative style of its syntax.

This means that the only thing left to do is to specify this trigger, which we can do by using a null_resource.

Quoting the official documentation:

The

null_resourceis a resource that allows you to configure provisioners that are not directly associated with a single existing resource.

Let’s jump straight into the code, which I believe will make everything clear:

variable "certificate_email" {}

resource "null_resource" "provision_openvpn" { triggers { subdomain_id = "${aws_route53_record.vpn.id}" }

connection { type = "ssh" host = "${aws_instance.openvpn.public_ip}" user = "${var.ssh_user}" private_key = "${var.private_key}" agent = false }

provisioner "remote-exec" { inline = [ "sudo apt-get install -y curl vim libltdl7 python3 python3-pip python software-properties-common unattended-upgrades", "sudo add-apt-repository -y ppa:certbot/certbot", "sudo apt-get -y update", "sudo apt-get -y install python-certbot certbot", "sudo service openvpnas stop", "sudo certbot certonly --standalone --non-interactive --agree-tos --email ${var.certificate_email} --domains ${var.subdomain_name} --pre-hook 'service openvpnas stop' --post-hook 'service openvpnas start'", "sudo ln -s -f /etc/letsencrypt/live/${var.subdomain_name}/cert.pem /usr/local/openvpn_as/etc/web-ssl/server.crt", "sudo ln -s -f /etc/letsencrypt/live/${var.subdomain_name}/privkey.pem /usr/local/openvpn_as/etc/web-ssl/server.key", "sudo service openvpnas start", ] }}As you can see at the very top of this snippet of code, we are declaring a null_resource that is triggered when the value aws_route53_record.vpn.id changes, which happens when the subdomain is created. When this happens, Terraform will execute the provisioning logic defined in the rest of the code here, which essentially describes to Terraform how to connect to the OpenVPN machine and what code needs to be run and which we already discussed in the first part of this article.

The provider configuration and the variable file

Ok, our setup is almost ready… The only two things we have left to do are:

- define the needed configuration to connect to our AWS account;

- define some values for our configuration before we can run Terraform.

To define the AWS config we need to specify the following terraform code (I generally do that into a dedicated file called provider.tf, but you can write this in any terraform file in your project):

variable "aws_profile_name" {}variable "aws_region" {}

provider "aws" { profile = "${var.aws_profile_name}" region = "${var.aws_region}"}Finally we can define the values for our variables. To do so we need to create a file called terraform.tfvars which contains a simple list of key-value pairs:

aws_profile_name = "default"aws_region = "eu-west-1"public_key = "${file("key.pub")}"private_key = "${file("key")}"route53_zone_name = "example.com."subdomain_name = "vpn.example.com"

# vpc_cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"# subnet_cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"# ssh_port = 22# ssh_cidr = "0.0.0.0/0"# https_port = 443# https_cidr = "0.0.0.0/0"# tcp_port = 943# tcp_cidr = "0.0.0.0/0"# udp_port = 1194# udp_cidr = "0.0.0.0/0"# subdomain_ttl = 60# ami = "ami-f53d7386"# instance_type = "t2.medium"# admin_user = "openvpn"# admin_password = "openvpn"The commented lines (starting with #) are left for your own reference, in case you want to change one of the configuration defaults.

Plan, apply and destroy

Ok, we are finally ready to run our Terraform project.

In order to see what changes will be applied to your AWS account, your will need to run:

terraform planIf you are happy with the displayed changes you can confirm them with:

terraform applyAfter few minutes you will have a fully provisioned Virtual Private Cloud with its own VPN access. Try to connect to the domain (https://vpn.example.com) and login in with your admin username and password!

Ok, this was probably just a test project for you so you might fancy cleaning everything up… No problem, just run:

terraform destroyand everything we just created will be blown away from your AWS account, leaving no trace behind!

Some extra tips

Just few extra tips before closing off…

Let’s Encrypt throttling

Let’s Encrypt allows you to generate a limited number of certificates for a given domain on a given timespan.

Quoting directly from the Let’s Encrypt Rate Limit documentation:

The main limit is Certificates per Registered Domain (20 per week). A registered domain is, generally speaking, the part of the domain you purchased from your domain name registrar. For instance, in the name www.example.com, the registered domain is example.com. In new.blog.example.co.uk, the registered domain is example.co.uk. We use the Public Suffix List to calculate the registered domain.

If you have a lot of subdomains, you may want to combine them into a single certificate, up to a limit of 100 Names per Certificate. Combined with the above limit, that means you can issue certificates containing up to 2,000 unique subdomains per week. A certificate with multiple names is often called a SAN certificate, or sometimes a UCC certificate.

We also have a Duplicate Certificate limit of 5 certificates per week. A certificate is considered a duplicate of an earlier certificate if they contain the exact same set of hostnames, ignoring capitalization and ordering of hostnames. For instance, if you requested a certificate for the names [www.example.com, example.com], you could request four more certificates for [www.example.com, example.com] during the week. If you changed the set of names by adding [blog.example.com], you would be able to request additional certificates.

So, be careful not to blow your production domain while playing with Terraform (or with certbot in general).

There are options to generate test or staging certificates, although I haven’t experimented much with them, so I can only suggest you to have a look at the documentation illustration all the available command line options.

Huge thanks to tialaramex on Reddit for a fruitful discussion and few pieces of advice about this specific aspect.

Certificate expiry and renewal

Let’s Encrypt certificates expire after 3 months, so be sure you enable the auto renewal feature.

In reality, the feature is enabled by default, so what’s left to do is to test the auto renewal process. With certbot you can do that using the following command:

certbot renew --dry-runThere’s another important point here to take into account here: everytime the certificate renewal procedure is triggered, your VPN service gets shutdown for few seconds and all the currently connected users are disconnected.

This will happen only once every 2-3 months, but if it’s a real struggle for your organisation you might want to explore different setups.

One solution could be to setup a reverse proxy like Nginx and use it for the SSL termination. This way during the renewal you will only shutdown nginx and not the full VPN service.

Thanks again to tialaramex on Reddit for raising this discussion and proposing the reverse proxy solution.

Intermittent failures during the provisioning

I had some problems during the installation of certbot on the image used here by default. If this is happening to you as well, you should be able to sort them out by running an apt-get upgrade before trying to install certbot. Since you want to do that in an automated fashion, you’ll probably need a more sophisticated command that takes care of auto-responding to possible prompts: yes | sudo DEBIAN_FRONTEND=noninteractive apt-get upgrade.

Wrapping up

This is just a quick example focused on OpenVPN, but you can use the same approach to generate certificates for other web applications. Consult the Certbot documentation to see all the supported web servers and how to use Certbot with them.

Also, I hope this tutorial gave you a good idea on how to use Terraform to automate your infrastructure provisioning. I am still a bit of noob with it, so if you see I have done something terribly wrong (or something that can be improved), please let me know in the comments.

Thanks to @Podgeypoos79, @techfort, Alan and the rest of Planet 9 tech team for working with me on this cool 💩 (chocolate ice cream!). Also a huge thanks to my friend @gianarb for some precious devopsy bits of advice.

Let me know in the comments if this article was useful for you and if you integrated something similar in one of your projects!

See you in the next post :)